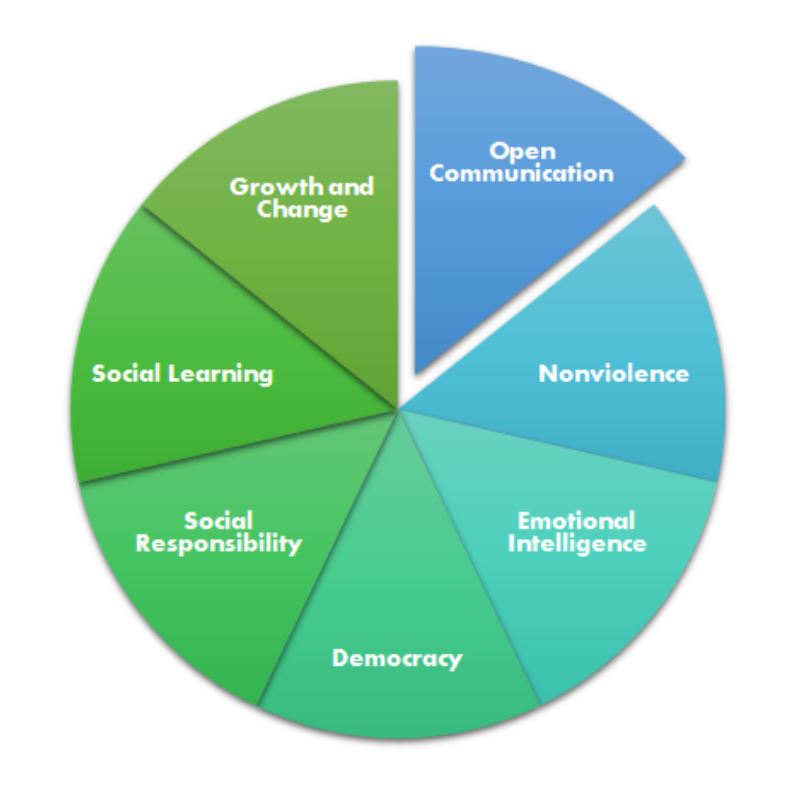

The Seven Commitments

The Seven Commitments:

Open Communication

Open communication seems great and sort of a no-brainer, but it may be a surprisingly challenging Sanctuary commitment. Lots of people may be familiar with how politicians and advertisers will use euphemisms to make something sound more, or less, palatable than it may actually be. If we were to talk about the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act would we have a different conversation than if I said Obamacare? Did you know that pharmaceutical companies hire researchers to conduct focus groups on names for their drugs? Skyrizi is much easier to say, remember, and feels more aspirational than Risankizumab. One of my preferred examples of this sort of activity is the marketing of names. Did you know that Ralph Lauren’s given name is Ralph Rueben Lifshitz? He talks about the change and why he used Lauren here, but I think you might be able to guess why someone trying to sell high-end clothing lines would prefer a less evocative moniker. My point here is that upon inspection we may be generally a lot less open with our communication than we might think.

Hopefully, that bit about Ralph Lauren gives you a chuckle. Delete with abandon or keep reading for how open communication shows up as a commitment in Sanctuary.

It can be very uncomfortable to communicate clearly, especially if we feel that the message won’t be well-received or that it will make the situation awkward. How often might we tell a loved one that we like their outfit when actually we do not? How often do we tell a friend or colleague that they have something in their teeth? If it is difficult in these situations, how much harder might it be then to have to be the bearer of a new rule, a change in something people like, or in addressing performance issues in a direct report?

We can be so uncomfortable with open communication that people who do communicate directly can get labeled difficult, bossy, authoritarian, and so on.

What does Sanctuary mean by open communication?

The Sanctuary Standards for Certification state that in regard to open communication, “Members agree to be aware of how they communicate with each other. Community members agree to talk about issues that affect the whole community, no matter how difficult they may be, and to do so in a direct and open way. Leaders practice transparency in regard to decisions or issues that affect everyone. All community members have the information they need to be successful.”

Let’s read that again.

Members agree to be aware of how they communicate with each other. Community members agree to talk about issues that affect the whole community, no matter how difficult they may be, and to do so in a direct and open way. Leaders practice transparency in regard to decisions or issues that affect everyone. All community members have the information they need to be successful.

Communication repeatedly comes up as an issue for The Wright Center and, frankly, just about every other organization on the planet. This is due in part to the lack of people on all sides of a communication using teach-back to make sure everyone has the information they need to be successful. It is also due in part to interpersonal static that can get in the way of open communication – static that can exist among leaders just as it exists anywhere else in an organization.

That static can, and usually does, exist anywhere that has people. We trigger one another all day long. We find ourselves having to make unfortunate and sometimes very nearly impossible decisions. Sometimes these choices feel like we don’t have a choice, but actually, we really do, they’re just crappy choices. (Even the happy endings of Disney movies often start with tragic loss).

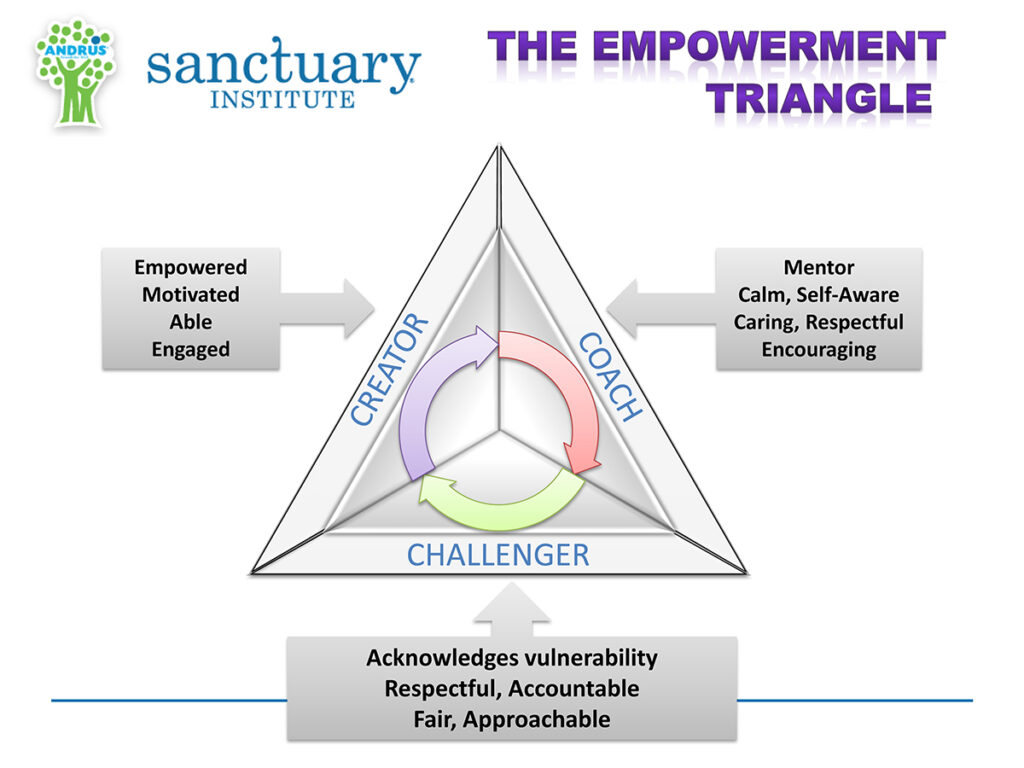

Some examples of challenging choices include agreeing to stay in health care during and after a pandemic, choosing to stay in a position that may make us feel uncomfortable (note: also applies to yoga), and choosing to not speak up when something needs to be addressed. Quitting a job and speaking up might feel very uncomfortable, but so too does working somewhere or in a position that really isn’t for us, or suffering the moral injury of continuing to engage in an action with which we wholly disagree. This sometimes extreme discomfort can itself be triggering, causing us to create reenactment triangles because we feel like a victim, which in turn leads us to the most convenient, though not necessarily accurate, persecutor.

There are two ends to every communication: sender and receiver. In this way, open communication is entirely entangled with emotional intelligence. Whether we are sending messaging or receiving them, awareness of our own triggers (words, phrases, issues, people, tones of voice, smells, could be anything) is essential to showing up in that communication ready to engage professionally and with reason, or, conversely, knowing that we can’t show up well in a given moment. Emotional intelligence similarly helps us to understand when we should, and shouldn’t, be making any big decisions.

In the weeks since I participated in a Sanctuary training, I cannot even tell you how many times I have felt angry, irritated, frustrated, and exhausted. I’m human, it happens. And I would bet that people who have been in certain meetings with me would attest to the fact that I do not always show up as my best self because, hey – it isn’t like we can turn our emotions off (and those of you who think you can, think again!). No one said this stuff would be easy. In fact, someone (*ahem*) has been saying all along specifically that it wouldn’t be.

None of these crucial conversations about performance, accountability, prioritizing, correcting errors, and fixing processes are really all that joyful. But they are necessary if we hope to get better at what we do. No one in such conversations is really having a ball; these types of conversations can actually be quite triggering. Being told we have done something incorrectly, that something isn’t quite as it should be is uncomfortable and can bring us back to a time and place where we were unjustly accused or were otherwise unsafe. From there we slip into a reenactment, and it can feel justifiable to rescue, persecute, or describe ourselves as a victim. It can feel really right to use big emotional language to describe something that felt bad, wrong, or otherwise yucky and point the finger everywhere but at ourselves. In these moments, in order to communicate openly, we have to actively exercise emotional intelligence to become aware that sometimes what feels right may really be a habitual drift into a reenactment.

Members agree to be aware of how they communicate with each other. Community members agree to talk about issues that affect the whole community, no matter how difficult they may be, and to do so in a direct and open way. Leaders practice transparency in regard to decisions or issues that affect everyone. All community members have the information they need to be successful.

Maybe committing right off the bat to open communication with everyone is too big of a first step. But I’m willing to bet that everyone in The Wright Center community can commit to ensuring at least one person they talk to this week has the information they need to be successful in at least one task. To paraphrase Louis Newman, over time, a change in even one degree becomes a new direction walked.

Quick Tips

(brought to you by Shannon Osborne)

Communication is a two-way street. We cannot control how someone delivers information but we can control (to the extent our triggers allow and practice coping with them) how we receive it. As we begin to get better at recognizing that we are triggered or otherwise reacting with irritation, frustration, anger, or fear in a conversation, we can take a secret few seconds to ourselves and spell some words backward in our head in order to bring the logical part of our brains back into the conversation. We can also take these secret little seconds to ask ourselves a question such as, “How do I want to show up in this situation?” (victim, rescuer, persecutor, or creator, challenger, coach).

Thank you,

Meaghan P. Ruddy, Ph.D.

Senior Vice President

Academic Affairs, Enterprise Assessment and Advancement,

and Chief Research and Development Officer

The Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education