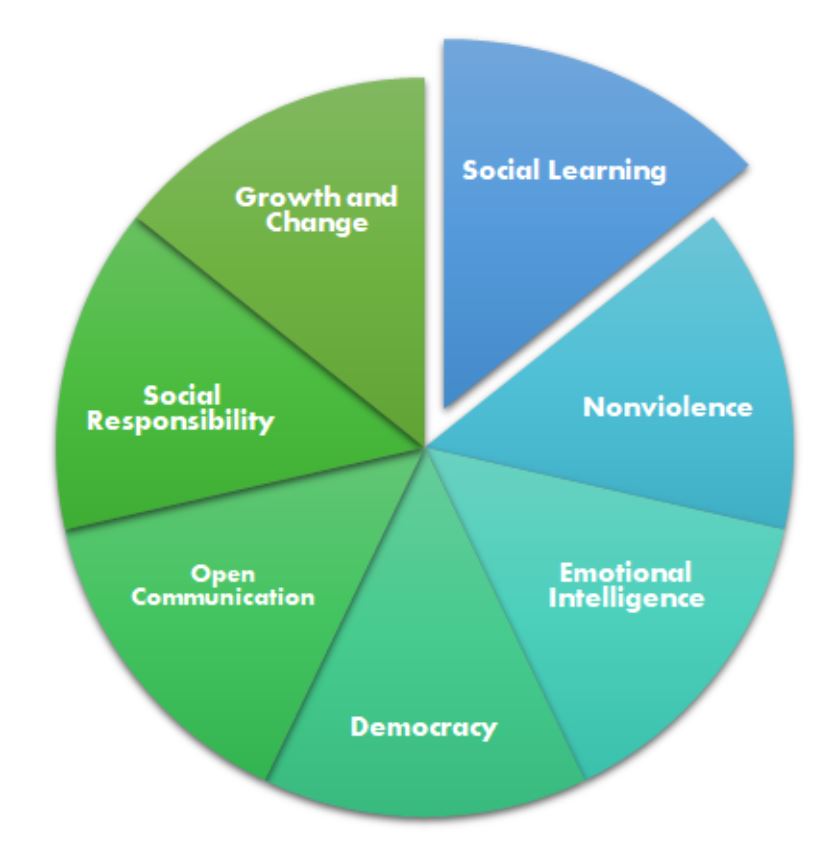

The Seven Commitments

The Seven Commitments: Social Learning

Learning can be scary. Seriously.

In order to learn, we have to admit we do not yet know. As professionals, it is difficult to admit we don’t know something – particularly those in clinical and/or leadership roles. Acknowledging we do not know something is to admit a level of vulnerability that is so uncomfortable it can – and often does – cross the line to feeling unsafe.

You can, of course, delete this and, I hope, go learn something today, or keep reading and learn right here about the commitment to Social Learning in Sanctuary.

Social learning is intentionally learning from one another. It can be intentional, like a work group, or informal such as chatting with colleagues and picking up tips and tricks. A Sanctuary organization intentionally creates an environment that allows people to learn from each other, their experiences, and their mistakes. Nonviolence, emotional intelligence, democracy, open communication, and social responsibility are all essential components of an environment wherein we can feel open enough to learn from one another.

The Sanctuary standards specifically call out practices such as using responses to disruptive or challenging incidents as opportunities for social learning via tools that Sanctuary calls red flag reviews as well as incident deconstruction and post-crisis analysis. Another practice the standards call out is disseminating and discussing the results of staff and client surveys in the community, such as during the Clinical Level 10 meetings. This can be an uncomfortable exercise as no one enjoys being associated with less-than-stellar results. However, social learning requires that we own both our successes and our shortcomings and that we are able to ask for input on ways to improve. It also helps the enterprise to understand where entire systems may be impacted by something. An individual here or there being behind on this or that is a much different circumstance than entire departments being behind or rated poorly on some metric.

Talking about pain points in a group setting can elicit input on fixes from others that we might not otherwise think about and gives us the chance to offer similar help to others, increasing opportunities for collegiality. Engaging in authentic social learning also helps supervisors, directors, and leaders to know where and how to focus their time and attention in that it may be an individual who needs some coaching or a whole workflow that needs revamping.

The word authentic is really important up there, hence the bold and underline. Authentic social learning can only happen when nonviolence, emotional intelligence, democracy, open communication, and social responsibility are also present. The advisee is less likely to take it in as help if the advice is offered with snark or diminishment. People are likely to feel called out and unsupported if survey results are just plowed through in order to check a box on a meeting agenda. Social learning requires engagement and, well, commitment from everyone involved.

The reason for this Sanctuary journey is a recognition that we’ve experienced trauma in our professional lives, and our professional community is our means of recovery. We’re either doing this, or we’re not. And if we’re doing this, we’re ALL doing this. Not just leadership, not just the people who are “into it.” Everyone. This includes those who feel they are being punished by being called out. Those who have said to their friends that so-and-so “isn’t doing Sanctuary.” Often people will do this because they feel so uncomfortable about a situation that their emotional reaction crosses the line to feeling unsafe.

A lot of this work, and I mean A LOT, is on the inside of each individual.

Yes, over the next three years or so, we will do things like make sure that performance reviews reflect a collaborative process between employee and supervisor, allowing for authentic input and feedback from the employee, and that the reviews include Sanctuary job expectations. We plan to do some art projects to create Sanctuary spaces, also part of the Sanctuary standards.

But none of that matters if we avoid speaking nonviolently with one another, using emotional intelligence when someone pushes our buttons, holding space for democratic airing of input, openly communicating our say even knowing we may not get our way, taking accountability for our responsibilities in our professional community, and creating opportunities to authentically learn from one another. These are called commitments for a reason. We are committing to actively engaging in these ways, especially when it is difficult. And if we really cannot commit, including holding one another accountable for doing so, we should take the initiative to ask the bus to slow down so we can get off.

I’d have a few bucks by now if I had a nickel for every time I said this Sanctuary journey was going to be a rough one. I don’t say that as a downer or even as a caution but rather as a level setter. Some people have come to me and, in one way or another, asked when the change will come. My typical answer is a reminder that this is a culture shift, and we’re on the path for at least three years. But, honestly, there is no magical date. There is no light-switch moment. There will be days, even five years from now when someone will have a real crap day and think, “Sanctuary my *$$.” Just as true, though, is that there are days happening for people right now, this week, where the change is already here.

I hope you have a day like that soon and when you do, you learn something really cool.

QUICK TIP

We learn in all kinds of ways all the time. Culturally we have made a business out of teaching and learning, called it education, and assigned it time periods and labels. This helps with some things but hinders others. Words like learner, student, and even resident come with implicit power differentials to teacher, preceptor, and faculty. This contributes to health care’s fairly toxic relationship to learning, despite a lot of lip service to the contrary.

So what can we do about it? Like health care itself, there is no quick fix truly worth investing in. Anything worth doing will take time. One thing we can do is work on becoming more comfortable with thinking of ourselves as lifelong learners. One way to do THAT is to work on our curiosity.

Language is a really important tool when working with trauma. Something we’ve addressed before is the difference between what’s wrong and what’s happening. This difference can help us to get into learning mode. Learning mode is curious mode, but getting curious (what’s happening) can be very difficult when we’re stressed out (what’s wrong).

Here is an activity that might help calm us down and help us find some curiosity.

Step 1: Find a quiet, comfortable place. Sitting, lying down, or standing up; just be able to concentrate without being distracted for a few moments.

Step 2: Recall your most recent run-in or incident with a stressful moment. Not too stressful, but something to practice this with. Remember the scene and relive that experience, focusing on what you felt at the time.

Step 3: Check in with your body. Ask yourself what is happening. What sensations can you feel most strongly?

Step 4: Notice where these sensations are in your body. We might have a tendency here to start on the what’s wrong stuff, but breathe and move back to what’s happening. Play with curiosity as much as you can. Is it more on the right side or the left? In the front, middle, or back? Does being a little curious change the relationship to this sensation? For example, maybe at first, you would have said it hurt, but after some curious exploring, you’d say it was uncomfortable or maybe warm.

Step 5: Explore what else you might be feeling and thinking. See if you can get curious and notice what else is there if the sensation is still there in your body. Are there other sensations you’re feeling? What happens when you get curious about them? Do they change? What happens when you get really curious about what they feel like? Do different thoughts come up? Different scenarios that maybe have nothing to do with the original one?

Step 6: Follow them over the next 30 seconds – not trying to do anything to or about them – but simply observing them. Do they change at all when you observe them with an attitude of curiosity?

Thank you,

Meaghan P. Ruddy, Ph.D.

Senior Vice President

Academic Affairs, Enterprise Assessment and Advancement,

and Chief Research and Development Officer

The Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education