Dombroskys share their story of organ donation for PA Donor Day on Aug. 1.

In the fall of 2013, Steve Dombrosky was out of breath seemingly all the time. A previously active 57-year-old, he struggled to get out of bed and go to his job as an electronics technician at the Tobyhanna Army Depot. His symptoms were not much better at work.

“It was a chore just to go to the restroom,” he recalls. “By the time I got back, I was almost gasping for air. I wasn’t walking; I was shuffling my feet.

Dombrosky and his wife, Pam, who’d spent 18 years working as a registered nurse, knew something wasn’t right. An initial doctor’s examination revealed a fatty liver diagnosis. After further testing, he was diagnosed with NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. NASH is the most severe form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and is closely related to obesity, pre-diabetes, and diabetes.

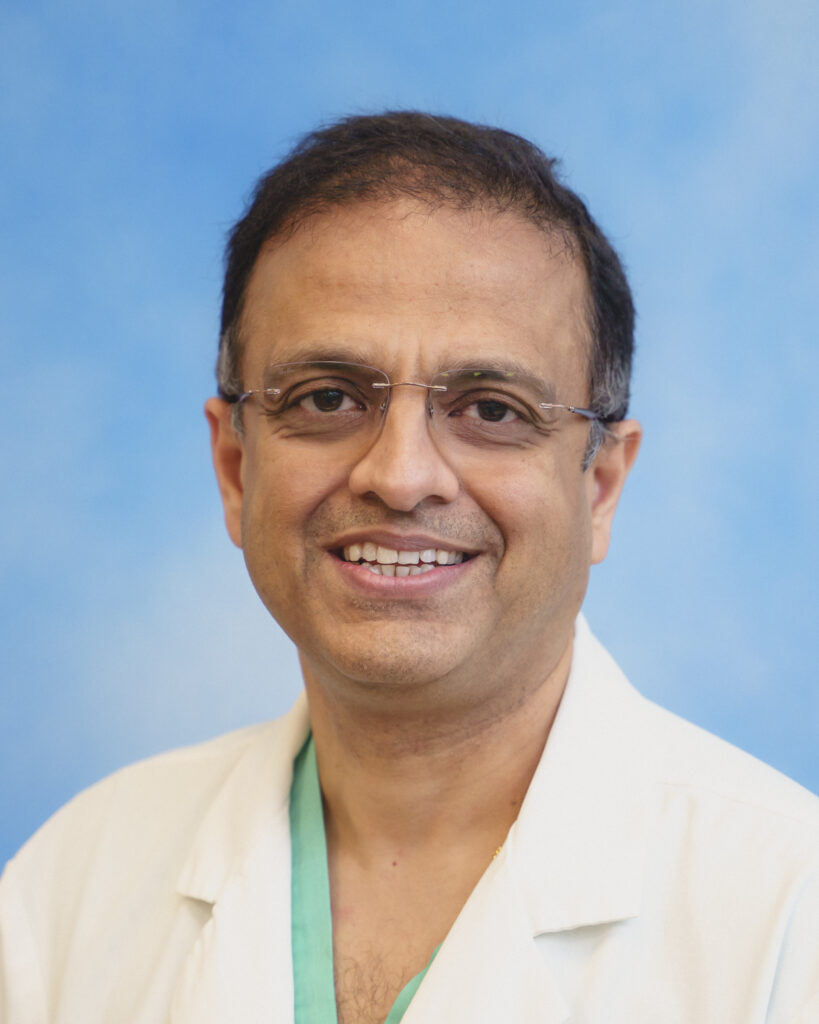

Steve and Pam Dombrosky are strong advocates for organ and tissue donations after they experienced the gift of life. In 2018, he received a lifesaving liver transplant due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis disease. Today, the couple is living life to the fullest, as exhibited in this photo at a recent wedding.

As the disease progressed, he experienced internal bleeding resulting in a dangerously low blood count. “I had many blood and iron transfusions. We were always running somewhere for treatments,” he said.

He would gain nearly 25 pounds each time his body retained fluids, making everyday tasks almost impossible to complete. During one hospital visit, doctors removed eight two-liter bottles of fluid from his abdomen. In April 2018, he was placed on the liver transplant list during a 15-day stay at Geisinger Health System in Danville.

“I fought it for five years. You have to be really sick to get on a transplant list. You have to be on the edge of saying goodbye before you’re put on a list,” he said.

Steve was placed on the transplant list and sent home on a Thursday. The next day he received a call with incredible news: They had a liver for him.

“I was coming home, and he called me, and he was crying,” Pam recalled. “I said, ‘why are you crying?’ and he just kept saying, ‘I got a liver, I got a liver.’ We could not believe how quick it was.”

The donor was a 24-year-old man who had chosen to be an organ donor. That man’s decision saved the lives of many people. It’s something the Dombroskys will never forget.

“We cried and cried for him; we grieved for him every day,” Pam said, overcome with emotion. “People need to become organ donors. There’s not much to it, just checking a box on your driver’s license.”

Steve wasn’t the first person on the list for the transplant. The first patient was too sick for the operation, and the second patient refused it due to the possibility of a hepatitis infection due to the donor’s age. Doctors explained to Steve that the chance of infection was minimal and that they were prepared to treat him for hepatitis if needed.

“People don’t get the chance that I got. I’ve always been sort of a gambler. I knew this was my shot. If I say no, I’m going to be a goner,” he said. “My name is not going to come back around on that list before I’ve passed away. There are days I feel 24 years old again, and I believe that’s from our donor.”

The Dombroskys encourage everyone to become organ donors.

“My thinking is, when the good Lord comes for you, he doesn’t want your body; he’s only coming for your soul,” said Steve. “So why not give the gift of life? If I could give someone eyesight, a heart, a kidney, or a skin graft, then there’s a part of me still living, and I think that’s just fantastic.”

Steve and Pam are both grateful to the donor and his family, as well as all of the medical professionals and organizations that have helped them on this journey.

They were among the first recipients of monetary support from The Cody Barrasse Memorial Foundation, a nonprofit organization founded by the family and friends of Cody Barrasse, a 22-year-old Moosic resident who died after being struck by a car. Barrasse was an organ donor; eight individuals received his life-saving organs. The foundation helps to offset the costs that many organ donor recipients face and supports a scholarship in his name at Scranton Preparatory School.

Steve and Pam Dombrosky are grateful for the gift of life after Steve received a lifesaving liver transplant in 2018 due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis disease. The couple received support from The Cody Barrasse memorial Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps to offset the costs of organ transplantation.

Steve, now 62, has combined his passion for cars with a part-time job, working for a friend with a small automotive dealership. He takes care of mostly everything around their home, including having dinner ready when Pam comes home from her job in the accounting department at The Wright Centers for Community Health and Graduate Medical Education in Scranton, where she started working during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Everyone has been wonderful – at CMC, in Danville, and here at The Wright Center,” said Pam. “When I read the email (at The Wright Center) about Organ Donor Awareness Month, I wanted to share our story.”

For anyone unsure of becoming an organ donor, Steve has one thing to say: “You can consider yourself a hero; you gave a better life to someone else, and that says a lot about who you are. It’s a never-ending battle for these people waiting on transplant lists, and you can help in so many ways,” he said.

For more information about organ donations and how to become an organ donor, visit the PA Donate Life website or the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT).