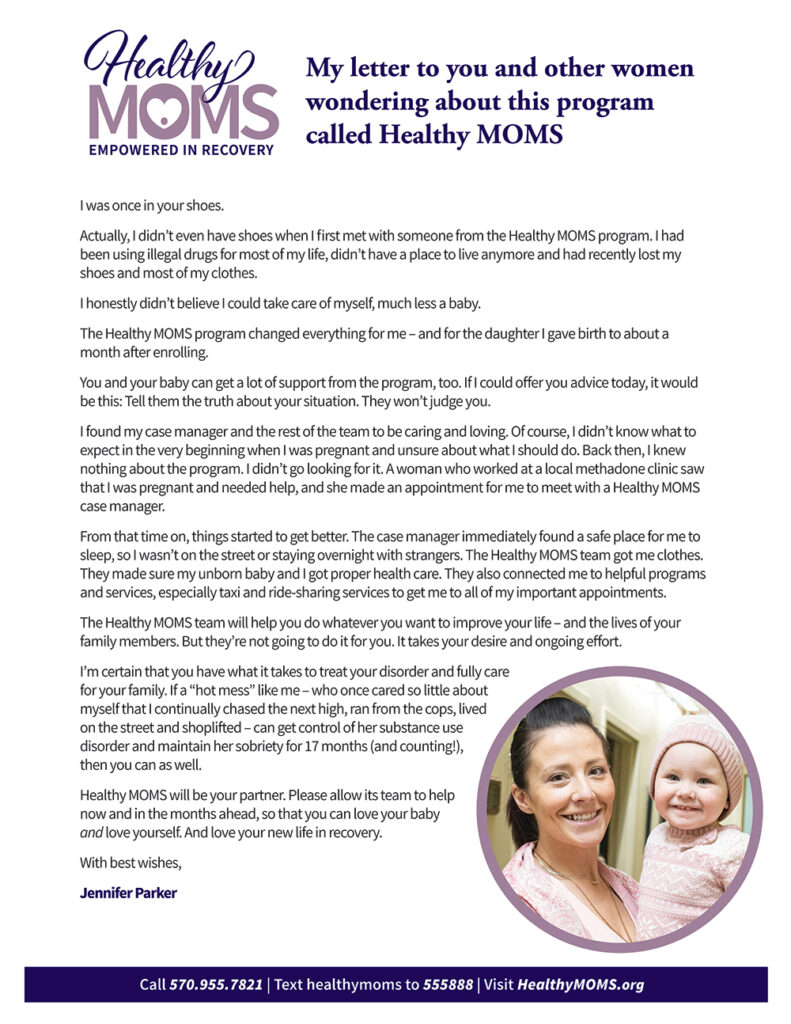

Michaelene Davis, of Olyphant, finds renewed joy in walking her dog Rosie and other daily activities that had become fatiguing before she shed more than 70 pounds through the Obesity Medicine initiative at The Wright Center for Community Health. ‘I saw tremendous positive results,’ she says.

Michaelene Davis, 69, recaptures joy of volunteering and other activities with assistance from The Wright Center’s obesity medicine services.

Michaelene Davis attributed her sore back and daytime sleepiness to all kinds of factors until, finally, her physician helped her to confront the real issue: unhealthy weight gain.

The Olyphant resident, a retiree and frequent volunteer at local animal rescues, knew she had added pounds in the four years immediately after her husband’s unexpected death – a jarring loss that happened on the day before their wedding anniversary. The connection between her empty heart and expanding waist didn’t hit home until a visit to The Wright Center for Community Health.

Dr. Linda Thomas-Hemak, a practicing physician who also is The Wright Center’s president and CEO, knew Davis’ health and family histories. As a result of the trusted relationship they had developed over the years, Thomas-Hemak recognized something was amiss with Davis during a COVID-19 vaccination-related exam and took the opportunity to urge her patient to reflect on her developing weight issue and its possible root causes.

Davis followed her doctor’s advice: She did some serious soul-searching at home and during a follow-up visit to further talk about the matter.

After receiving weight-loss assistance from The Wright Center for Community Health, retiree Michaelene Davis is no longer held back by symptoms such as a sore back, achy joints and daytime sleepiness.

“It was an epiphany,” says Davis, 69. “I had been using the food as comfort.”

“And the more comfortable I got,” she explains, “the more comfortable I wanted to be. It wasn’t that I didn’t know the good, nutritious things to eat. I just didn’t care and didn’t take the time to prepare them. I was strictly looking for what would make me happy right at that moment.” The patient and her physician, who was then studying to become board certified in obesity medicine, worked cooperatively to draw up a treatment plan. Davis made immediate changes to her eating habits, chiefly by decreasing intake of her go-to dish and admitted “downfall:” pasta. Soon after, she also began taking medications to control her blood sugar, which in turn soothed her wild cravings for carbs.

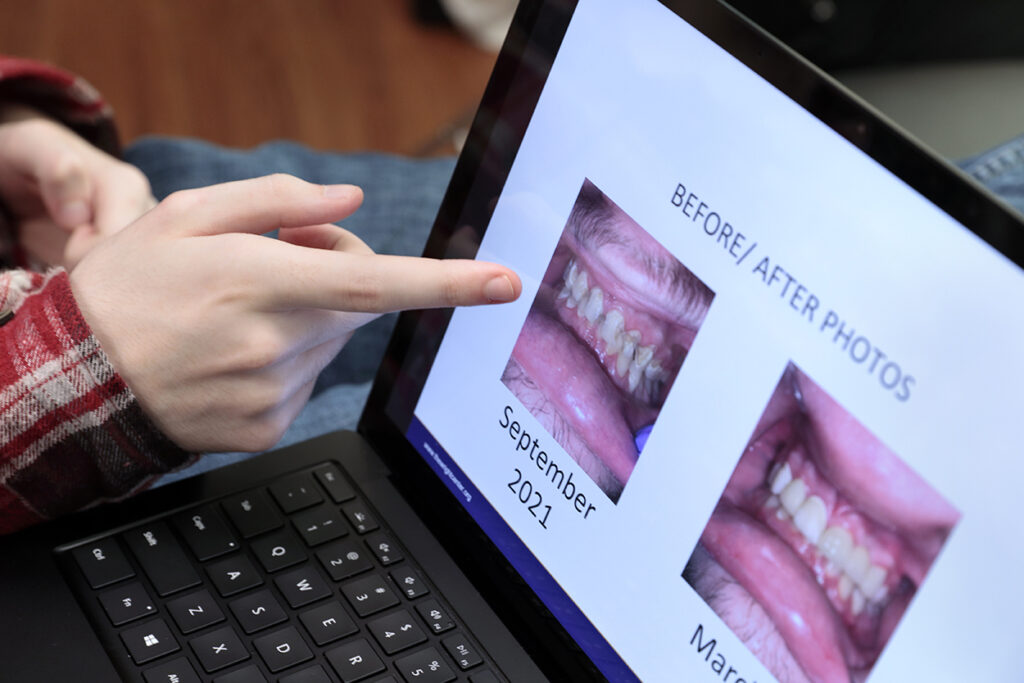

Since making those adjustments in her life, Davis has shed more than 70 pounds. Plus, as she is quick to point out, she is on a far better health trajectory. The results of her A1c tests – which are used to measure a person’s average blood sugar levels over the prior two to three months – have dropped from 6.9 percent (diabetic range) to 5.3 percent (normal range).

“I saw tremendous positive results,” Davis says. And she can feel the difference, too, she says. No more need for an afternoon nap. No more consistently sore back and aching joints.

Today, Davis can again haul grocery bags up her garage stairs to the kitchen without pausing every two to three steps to huff and puff. She walks her two dogs, Rosie, a boxer, and Taz, a pitbull, with ease, enjoying each outing rather than viewing it as an obligation.

Even her volunteer hours spent at local animal rescue organizations – Adopt A Boxer Rescue in Olyphant and Friends with Paws Pet Rescue in Scranton – have a renewed sense of joy. “I can get down on the floor and play with the dogs, then jump back up and move on, whereas before all of that was a struggle,” she says. “The funny part is, while I was struggling, I knew I was having difficulty, but I wasn’t seeing it for what it truly was.”

Confronting complex disease

Obesity – the nation’s most prevalent chronic disease – is associated with several of the leading causes of preventable, premature death, yet physicians and patients are sometimes hesitant to directly address the sensitive topic and tailor plans that allow for long-term success.

Obesity medicine is an emerging specialty, and its practitioners consider that excessive weight gain can be caused by multiple, sometimes intertwined, factors: genetic, nutritional, environmental and behavioral.

The Wright Center for Community Health recognizes the complexity of the issue and now offers obesity medicine services, aiming to improve outcomes for patients by combining evidenced- based methods with individualized treatment plans.

The Wright Center’s two American Board of Obesity Medicine-certified physicians – Dr. Jumee Barooah and Thomas-Hemak – and other providers use non-surgical approaches to help individuals better manage, care for and overcome obesity. “By recognizing obesity as a multifactorial disease, and removing bias from the equation, today’s medical professionals increasingly are prepared to give patients the facts and the tools they need to take charge of their health,” Dr. Barooah says.

For Davis, coping with excessive weight hadn’t begun in childhood or even young adulthood. Instead, the situation crept up on her late in life, after the sudden loss of her husband, Bill Davis, a construction worker and avid bowler, in 2017. Michaelene Davis didn’t sink into depression, she says, as much as a prolonged “pity party.” To handle the shock and loneliness of the situation, she sought solace in comfort foods. Doughy pierogis. Noodle-laden haluski. Other white flour-filled pastas. Rich sauces and soups.

Her weight gain compounded during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic and long stretches of relative inactivity as she hunkered down at home, she says. Eating solo, she often gulped her meals in only a few minutes instead of savoring them.

As part of her weight-loss journey, she decided to change that pattern and slow down the consumption of her evening meals. “I’m an avid reader,” she says. “So, I worked out a system where I’d cut my piece of fish or chicken, and I’d eat it and then I’d put down my fork and I’d read a little on my Kindle. I kind of relaxed and slowed my tempo, and that worked well for me.”

Michaelene Davis experienced unhealthy weight gain later in life, after the sudden and unexpected loss of her husband. ‘I had been using the food as comfort,’ she says. Today she has dropped the extra pounds and embraced a better diet, even making her own low-sugar salad dressings.

Quieting the ‘demons’

Davis, of course, wasn’t alone in determining how to adopt healthier eating habits.

She benefited from The Wright Center’s team-based approach to health care, meeting regularly with Thomas-Hemak and scheduling two consultations with registered dietitian Walter Wanas, the organization’s director of lifestyle modification and preventive medicine. Wanas spoke to her about choosing the right foods based on their ranking in the glycemic index – a system for gauging how fast and how high certain foods tend to raise blood sugar.

In the earliest days of her treatment, Davis had battled food cravings that she wrongly blamed on poor willpower. Turns out, the problem was metabolic.

“I had become insulin resistant,” says Davis. “Correcting my diet, along with starting the medication, turned my insulin resistance around, which quieted the demons in my head that werescreaming for those carbs.”

Based on Davis’ new understanding of the glycemic index, she started hunting for online resources to find the best food choices. She even began experimenting with recipes, for example opting to make her own salad dressing rather than reach for the sugary, store-bought varieties.

She reintroduced fruits and vegetables into every meal. Now she frequently makes fish the centerpiece of a meal and, if she adds pasta to the menu, uses it only in proper proportions. And if she goes out for a treat, it’s often not to a restaurant but rather a retail store where she can look for clothes in sizes that fit her slimmer figure.

“Now instead of being comforted by food,” she says, “I get comforted shopping for a new pair of jeans!”

For more information about The Wright Center’s obesity medicine services, call 570.230.0019 or visit TheWrightCenter.org/services.