Inspirational images from people living in recovery and others serve to promote healing amid prolonged pandemic

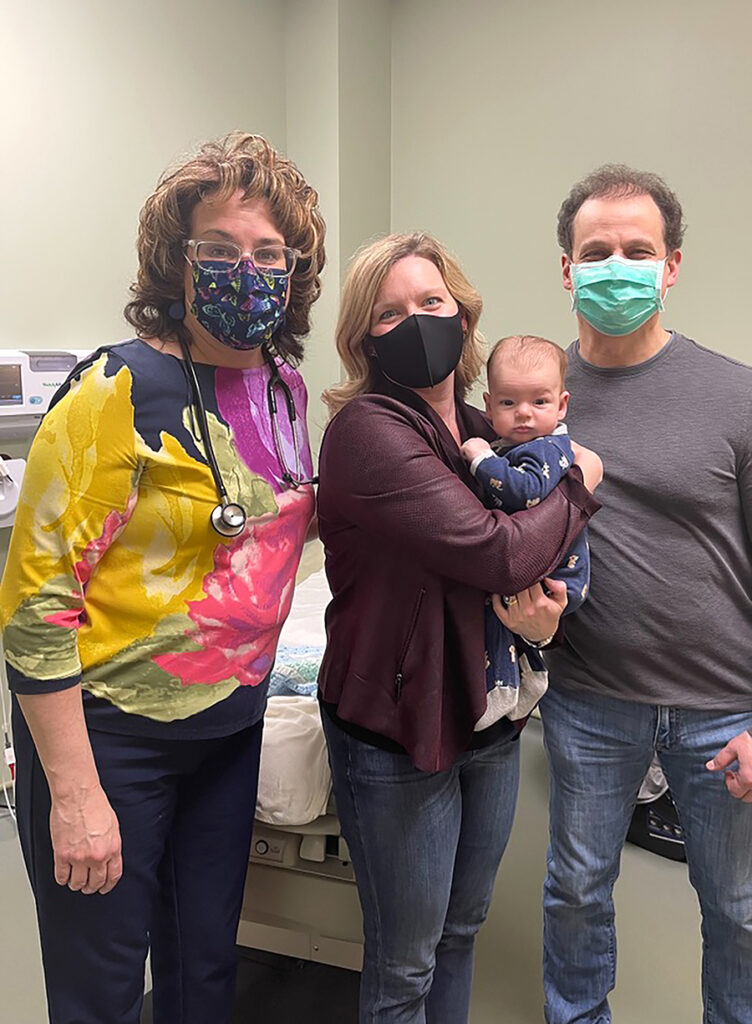

Scranton, Pa. (Nov. 23, 2021) – Looking at the ho-hum hallways in The Wright Center for Community Health’s Clarks Summit Practice, Dr. William Dempsey and his colleagues saw an opportunity to give a platform to patients – and just maybe help them to heal.

They asked patients and employees to share personal photographs with deep meaning, the sort of cellphone images that capture an inspiring scene, a significant life moment, a milestone. They particularly wanted to receive and spotlight photos from people who cope with substance use disorders, such as addiction to opioids.

The result: a fast-growing photo collection that reflects pieces of our shared humanity, from its emotional messiness to everyday majesty.

“These photos capture the spiritual part of the journey that our patients are on,” says Dempsey, deputy chief medical officer of The Wright Center and medical director of its Clarks Summit Practice. “We ask each person who submits a photo to tell their story. What’s the message your photo conveys? When you took the photo, what was the subject saying to you? That’s what we’re trying to get.”

One stark photograph zooms in on a snow-covered patch of ground and a few items that could be mistaken for litter: a Campbell’s Chunky soup can and an empty water bottle. The patient calls this image “My Last Meal as an Addict.”

About 40 photographs have been framed and mounted so far, hinting at what promises to become a vast collection of eye-catching and discussion-spurring art. “We’re going to fill the walls,” says Carlie Kropp, a case manager for The Wright Center’s Opioid Use Disorder Center of Excellence.

Kropp, who teamed with Dempsey to launch the photo project, intends to soon plug more pieces into bare spots in the patient waiting area and long corridors leading to exam rooms. Over time, she expects this, as-yet unnamed, collection to continually evolve as pieces get rotated out to accommodate new submissions.

“We want anyone who wants to participate to do so,” says Kropp, a Shavertown resident. “We want the clinic to feel warm and welcoming, and to promote a community where we all care about each other.”

She and Dempsey say the photo project offers multiple benefits, from sparking conversations about important topics with patients who are living in recovery, to reducing stigma surrounding addiction, to making the clinic’s interior a bit more attractive.

Each photo will be displayed with a label and brief message, giving its creator a voice to explain the shot and its significance. A flower with vibrant pinks and yellows, for example, fills one frame, representing one patient’s self-described experience of “Blooming Again,” Kropp says.

Nature is a common theme of several photos: a rainbow emerging after a storm, trees reflected in placid water, a sunrise. Collectively, the participants shared shots evoking happiness, heartache and perhaps the most important “H” of all: hope.

For Kropp, the ongoing photo project might be just the salve needed to help relieve some of the sting inflicted by the COVID-19 pandemic. “When you are living with a mental health diagnosis, or an addiction, isolation can really hurt,” she says. “This photo initiative is just kind of keeping us united and giving us faith that things will turn around, and we’ll get back to regular life.”

Meanwhile, if walls could talk at the Clarks Summit Practice, the dialogue would reveal a tussle between sickness and health, which in many of the newly hung photos is represented by darkness and light.

The light-dark contrast is evident, for instance, in a photo of a waning moon. It also dominates an image contributed by Dempsey and taken on the forested edge of a local reservoir shortly after a destructive spring storm. “In the back you can see the darkness, symbolizing addiction, and then you can see the crystal clarity of the water,” he says. “So, I named that photo ‘Recovery Begins.’”

Dempsey took inspiration from that image to start the clinic’s collective photo display, aiming to reawaken spirituality and optimism in the lives of his patients who struggle with substance use disorder. “The photos give me a point of reference to have that discussion,” he says.

“I advise my patients: ‘Go out there and find your spirituality,’” Dempsey says. “‘And when you do, get a picture of it and share it with us.’”

Patients of The Wright Center for Community Health’s Clarks Summit Practice can submit photos for consideration by sending an email to case manager Carlie Kropp, at kroppc@thewrightcenter.org. Or call her at 570.507.3608.